Arun Kolatkar pictured at the Wayside Inn, Kala Ghoda, Bombay, 1995 (photo: Madhu Kapparath).

Arun Kolatkar (1931-2004) was one of India’s greatest modern poets. He wrote prolifically, in both Marathi and English, publishing in magazines and anthologies from 1955, but did not bring out a book of poems until he was 44. His first book of poetry,

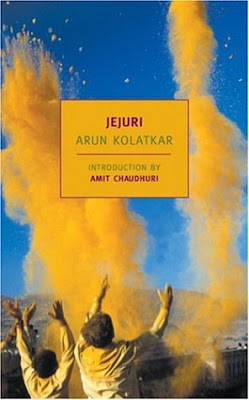

Jejuri (1976), won him the Commonwealth Poetry Prize. His third Marathi publication,

Bhijki Vahi, won a Sahitya Akademi Award in 2004. Both an epic poem, or sequence, celebrating life in the Indian city (and site of pilgrimage) of that name in the state of Maharashtra,

Jejuri was later published in the US in the NYRB Classics series, with an introduction by Amit Chaudhuri, an edited version of which was published by

The Guardian in 2006: see

this link for Chaudhuri's account of 'the poet who deserves to be as well-known as Salman Rushdie'.

Always hesitant about publishing his work, Kolatkar waited until 2004, when he knew he was dying from cancer, before bringing out two further books,

Kala Ghoda Poems (a portrait of all life happening in Kala Ghoda, his favourite street) and

Sarpa Satra. A posthumous selection,

The Boatride and Other Poems (2008), edited by his friend, the poet and critic Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, contained his previous uncollected English poems as well as translations of his Marathi poems; among the book’s surprises were his translations of bhakti poetry, song lyrics, and a long love poem, the only one he wrote, cleverly disguised as light verse. Arun Kolatkar's

Collected Poems in English, published by Bloodaxe Books in 2010, also edited by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, brought together work from the four volumes published in India by Ashok Shahane at Pras Prakashan.

Jejuri offers a rich description of India while at the same time performing a complex act of devotion, discovering the divine trace in a degenerate world. Salman Rushdie called it ‘sprightly, clear-sighted, deeply felt…a modern classic’. For Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, it was ‘among the finest single poems written in India in the last forty years…it surprises by revealing the familiar, the hidden that is always before us’.

Jeet Thayil attributed its popularity in India to ‘the Kolatkarean voice: unhurried, lit with whimsy, unpretentious even when making learned literary or mythological allusions. And whatever the poet’s eye alights on – particularly the odd, the misshapen, and the famished – receives the gift of close attention.’

Although the four volumes which comprise the

Collected Poems in English have been published in India, the book itself has not yet been published there, and for the moment Indian readers have had to buy copies of the Bloodaxe edition from the Strand Bookstore in Mumbai.

The Independent's literary editor Boyd Tonkin made it one of his books of the year in 2010: 'My discovery of the year arrived from India, in

Collected Poems in English by Arun Kolatkar. Sublime and satirical, comic and visionary by turns, close to the gutter but looking at the stars, Kolatkar over many years became a Bombay bard to march, or outperform, the city's novelists. Any reader of

Midnight's Children, and of its tribe of fictional children, should get to know Kolatkar too.' And writing in

The Tablet, Michael Glover said: 'The best new discovery of the season is…

Collected Poems in English by Arun Kolatkar, one of the great poets of post-war India… The poetry is utterly fearless. No topic is out of bounds… What is so delightfully unexpected, always, is his angle of attack. You can never quite prejudge how he will view the odd, improverished particularities of the topsy-turvy world that he studies with such care and irreverent fondness.' Stephen Knight, reviewing the book for

Poetry Review, declared that '

Collected Poems in English must already be regarded as a classic of English language poetry from India. In time, if there is any justice, its reputation will cross the globe.'

Regrettably, this work by a literary genius of world stature – a landmark in modern Indian literature – has not received very much attention in Britain, apart from those three notices and a few reviews, published or imminent, in the poetry magazines and journals. Even in India, Arun Kolatkar's profile was never as high as that of the much more widely published Nissim Ezekiel and Dom Moraes, but the

Collected Poems in English should establish his reputation as – to quote Michael Glover – 'one of the great poets of post-war India', in English as well as in Marathi.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra introduces the

Collected Poems in English with a marvellous essay, 'Death of a Poet', prefaced by his 'Editor's Note'. These two pieces form the best possible introduction to Kolatkar's life and work.

Arvind Krishna Mehrota, Colaba, Bombay, 1997

(photo: Madhu Kapparath).

ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA: EDITOR'S NOTE

Sometime in early 1967, in a Colaba Causeway bookshop in Bombay, I first set eyes on Arun Kolatkar. I had arrived in the city the previous year from Allahabad to do my MA at the university. Before coming to Bombay I had, as an undergraduate, written some poems and with two friends started a ‘little magazine’, a cyclostyled affair of which a couple of issues had appeared. It was called

damn you/a magazine of the arts. I was twenty years old.

I did not know Kolatkar but had heard about him from other poets and was keen to make his acquaintance. The man in the Causeway bookshop, with his long hair, drooping moustache, large slightly hooded raptorial eyes, and distinctive clothes – five-pocket jeans, round neck t-shirt, white khadi

bundi, fitted the mental image I had of Kolatkar, but before I could gather the courage to walk up to him and introduce myself he was gone. I must have met him soon afterwards, and either on that occasion or later I asked him for a contribution for damn you. He said I should come home with him, and we took a taxi from wherever we were in Flora Fountain to his flat behind the Colaba Post Office, where he lived with his first wife Darshan. It was here, without any fuss, that he gave me the manuscript of

the boatride, each section on a separate sheet and typed in capital letters, which is how it appeared in

damn you # 6 in 1968. It was to be the last issue of the magazine. Little could I have then imagined that thirty-seven years after he gave me the poem I would be sitting by his deathbed in Pune and he would ask me to edit his posthumous book of uncollected work,

The Boatride and Other Poems. That story is told in the Introduction; my association with him, the only ‘complete man of genius’ (Baudelaire’s phrase for Delacroix) I’ve known, had come full circle. (Incidentally, the many similarities between Kolatkar’s and Delacroix’s ‘Life and Art’, as described by Baudelaire in his magnificent essay on the painter, are uncanny.)

All his life Kolatkar had an inexplicable dread of publishers’ contracts, refusing to sign them. This made his work difficult to come by, even in India.

Jejuri was first published by a small co-operative, Clearing House, of which he was a part, and thereafter it was kept in print by his old friend, Ashok Shahane, who set up Pras Prakashan with the sole purpose of publishing Kolatkar’s first Marathi collection

Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita. In the event, Shahane ended up as publisher of both Kolatkar’s English and Marathi books, which together come to ten titles to date, with more forthcoming, including a newly-discovered Marathi version of

Jejuri, a book of interviews, and a novel in English.

The small press, despite the obvious limitations, suited Kolatkar. He was, for one, in complete control of the way the book looked, from its format (he did not want his long lines to be broken), cover design, endpapers, and blurb to what went on the spine, which in the case of

Kala Ghoda Poems and

Sarpa Satra was precisely nothing, no title, no author’s name, no publisher’s logo. Moreover, with Clearing House and Pras there were no contracts to sign. From time to time, trade publishers would send Kolatkar feelers to see if he was willing to part with

Jejuri, but making him change his mind wasn’t easy. One such occasion, when he was trying to get Kolatkar to sign an earlier contract, is described by Amit Chaudhuri in his Introduction to the NYRB Classics edition of

Jejuri, which Kolatkar gave permission for months before he died.

At one point, I was interviewed at the inn [Wayside Inn] by a group of friends, including Shahane – a sort of grilling by the ‘firm’ – while Kolatkar occasionally played, in a deadpan way, my advocate. His questions and prevarications regarding the contract betrayed a fiendish ingeniousness: ‘It says the book won’t be published in Australia. But I said nothing about Australia.’ Only my reassurance, ‘I’ve looked at the contract and I’d sign it without any doubts in your place,’ made him tranquil.

The four books that comprise the

Collected Poems in English appear in the order in which they were published. Though

The Boatride and Other Poems contains some of his earliest poems, it seemed proper to open a collected volume with

Jejuri, which was Kolatkar’s first book and the work he is most associated with. There comes a time in the life – or afterlife – of every cult figure when, escaping from the small group of readers that had kept the flame burning, mainly through word of mouth, he begins to belong to a larger world. With the publication of

Collected Poems in English, Kolatkar’s moment has perhaps come.

Arun Kolatkar (photo: Gowri Ramnarayan).

ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA: DEATH OF A POET

Arun Kolatkar, who is widely regarded as one of the great Indian poets of the last century, was born in Kolhapur, Maharashtra in 1931. His father was an educationist, and after a stint as the principal of a local school he taught at a teacher’s training college in the same city. ‘He liked nothing better in life than to meet a truly unteachable object,’ Kolatkar once said about him. In an unpublished autobiographical essay which he read at the Festival of India in Stockholm in 1987, Kolatkar describes the house in Kolhapur where he spent his first eighteen years:

I grew up in a house with nine rooms that were arranged, well almost, like a house of cards. Five in a row on the ground, topped by three on the first, and one on the second floor.

The place wasn’t quite as cheerful as playing cards, though. Or as colourful. All the rooms had mudfloors which had to be plastered with cowdung every week to keep them in good repair. All the walls were painted, or rather distempered, in some indeterminate colour which I can only describe as a lighter shade of sulphurous yellow.

It was in one of these rooms – his father’s study on the first floor – that Kolatkar found ‘a hidden treasure’. It consisted of

three or four packets of glossy black and white picture postcards showing the monuments and architectural marvels of Greece, as well as sculptures from the various museums of Italy and France.

As I sat in my father’s chair, examining the contents of his drawers, it was inevitable that I should’ve been introduced to the finest achievements of Baroque and Renaissance art, the works of people like Bernini and Michaelangelo, and I spent long hours spellbound by their art.

But at the same time I must make a confession. The European girls disappointed me. They have beautiful faces, great figures, and they showed it all. But there was nothing to see. I looked blankly at their smooth, creaseless, and apparently scratch-resistant crotches, sighed, and moved on to the next picture.

The boys, too. They let it al hang out, but were hardly what you might call well-hung. David, for example. Was it David? Great muscles, great body, but his penis was like a tiny little mouse. Move on. Next picture.

After matriculating in 1947, Kolatkar attended art school in Kolhapur, and, in 1949, joined the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay. He abandoned it two years later, midway through the course, but went back in 1957, when he completed the assignments and, finally, took the diploma in painting. The same year he joined Ajanta Advertising as visualiser, and quickly established himself in the profession which, in 1989, inducted him into the hall of fame for lifetime achievement.

Kolatkar also led another life, and took great care to keep the two lives separate. His poet friends were scarcely aware of the advertising legend in their midst, for he never spoke to them about his prize-winning ad campaigns or the agencies he did them for. His first poems started appearing in English and Marathi magazines in the early 1950s and he continued to write in both languages for the next fifty years, creating two independent and equally significant bodies of work. Occasionally he made jottings, in which he wondered about the strange bilingual creature he was:

I have a pen in my possession

which writes in 2 languages

and draws in one

__

My pencil is sharpened at both ends

I use one end to write in Marathi

the other in English

__

what I write with one end

comes out as English

what I write with the other

comes out as Marathi

Pilgrims at the Khandoba temple in Jejuri.

His first book in English,

Jejuri, a sequence of thirty-one poems based on a visit to a temple town of the same name near Pune, appeared in 1976 to instant acclaim, winning the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and establishing his international reputation. The main attraction of Jejuri is the Khandoba temple, a folk god popular with the nomadic and pastoral communities of Maharashtra and north Karnataka. Only incidentally, though, is

Jejuri about a temple town or matters of faith. At its heart, and at the heart of all of Kolatkar’s work, lies a moral vision, whose basis is the things of this world, precisely, rapturously observed. So, a common doorstep is revealed to be a pillar on its side, ‘Yes. / That’s what it is’; the eight-arm-goddess, once you begin to count, has eighteen arms; and the rundown Maruti temple, where nobody comes to worship but is home to a mongrel bitch and her puppies, is, for that reason, ‘nothing less than the house of god.’ The matter of fact tone, bemused, seemingly offhand, is easy to get wrong, and Kolatkar’s Marathi critics got it badly wrong, finding it to be cold, flippant, at best sceptical. They were forgetting, of course, that the clarity of Kolatkar’s observations would not be possible without abundant sympathy for the person or animal (or even inanimate object) being observed; forgetting, too, that without abundant sympathy for what was being observed, the poems would not be the acts of attention they are.

Far from mocking what he sees, Kolatkar is divinely struck by everything before him, as much by the faith of the pilgrims who come to worship at Jejuri’s shrines as by the shrines themselves, one of which happens to be not shrine at all:

The door was open.

Manohar thought

It was one more temple.

He looked inside.

Wondering

which god he was going to find.

He quickly turned away

when a wide eyed calf

looked back at him.

It isn’t another temple,

he said,

it’s just a cowshed.

(‘Manohar’)

The award of the prize inevitably led to interviews, which, except for the interview Eunice de Souza did later, are the only ones Kolatkar ever gave. In one interview, to a Marathi little magazine that brought out a special issue on him, Kolatkar was asked about his favourite poets and writers. ‘You want me to give you their names?’ he replied, and then proceeded to enumerate them:

Whitman, Mardhekar, Manmohan, Eliot, Pound, Auden, Hart Crane, Dylan Thomas, Kafka, Baudelaire, Heine, Catullus, Villon, Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Janabai, Eknath, Tukaram, Wang Wei, Tu Fu, Han Shan, Ram Joshi, Honaji, Mandelstam, Dostoevsky, Gogol, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Babel, Apollinaire, Breton, Brecht, Neruda, Ginsberg, Barth, Duras, Joseph Heller, Günter Grass, Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, Nabokov, Namdev Dhasal, Patthe Bapurav, Rabelais, Apuleius, Rex Stout, Agatha Christie, Robert Shakley, Harlan Ellison, Bhalchandra Nemade, Dürrenmatt, Arp, Cummings, Lewis Carroll, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Godse Bhatji, Morgenstern, Chakradhar, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Balwantbuva, Kierkegaard, Lenny Bruce, Bahinabai Chaudhari, Kabir, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, Howling Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Leiber and Stoller, Larry Williams, Lightning Hopkins, Andrzej Wajda, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, Truffaut, Woody Guthrie, Laurel and Hardy.

‘The astonishing admixture (off the top of his head),’ the American scholar of Marathi Philip Engblom has said of the list, ‘not only of nationalities but of artistic genres (symboliste poetry to art film to Mississippi and Chicago Blues to Marathi

sants) speaks volumes about the environment in which Kolatkar produced his own poetry’.

And not just Kolatkar. In the introduction to his

Anthology of Marathi Poetry: 1945-1965 (1967), in which some of Kolatkar’s best-known early poems like ‘Woman’ and ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’ first appeared, Dilip Chitre writes about ‘the paperback revolution’ which

unleashed a tremendous variety of…influences [that] ranged from classical Greek and Chinese to contemporary French, German, Spanish, Russian and Italian. The intellectual proletariat that was the product of the rise in literacy was exposed to these diverse influences. A pan-literary context was created.

[…]

Cross-pollination bears strange fruits. [Bal Sitaram] Mardhekar wrote books on literary criticism and aesthetic theory which make references to contacts with various European works of art and literature… During his formative years as a writer, he was deeply influenced by Joyce and Eliot, and these continued to be critical influences in his critical writing throughout his career, until his untimely death in 1956.

After the success of

Jejuri, except for the odd poem in a magazine, Kolatkar did not publish anything. To friends who visited him, he would sometimes read from whatever he was working on at the time, but there were to be no further volumes. Then in July 2004 he brought out

Kala Ghoda Poems and

Sarpa Satra. At a function held at the National Centre for the Performing Arts’ Little Theatre in Bombay, five poets read from the two books. Kolatkar, wearing a black t-shirt and brown corduroy trousers, sat in the audience. He was by then terminally ill with stomach cancer and did not have long to live.

To his readers it must have seemed at the time, as it did to me, that the publication of these long awaited new books by Kolatkar, twenty-eight years after he published

Jejuri, completed his English oeuvre. There were some scattered uncollected poems of course, most notably the long poem ‘the boatride’, but they had appeared in magazines and anthologies before and in any case were not enough to make another full-length collection. Which is why when Ashok Shahane, Kolatkar’s publisher, first brought up the idea of

The Boatride and Other Poems and asked me to draw up a list of things to include in it I was sceptical. In the event, the list, based on what was available on my shelves, did not look as meagre as I had feared. It had thirty-two poems divided into three sections: ‘Poems in English’, which had poems written originally in English; ‘Poems in Marathi’, which had poems written originally in Marathi but which he translated into English; and ‘Translations’, which had translations of Marathi bhakti poets, mostly of Tukaram. The first poem in the first section was ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’, written in 1953. A poem titled ‘A Prostitute on a Pilgrimage to Pandharpur Visits the Photographer’s Tent During the Annual Ashadhi Fair’, from his Marathi book

Chirimiri, was from the 1980s.

The Boatride and Other Poems, I remember thinking to myself, though small in terms of the number of pages, would be the only book to represent all the decades of Kolatkar’s writing life barring the last and the only one to have, between the same covers, his English and Marathi poems. Kolatkar approved of the selection when we discussed it over the phone and made one suggestion, which was to put ‘the boatride’ not with the ‘Poems in English’, as I had done, but at the end of the book, in a section of its own. The reason for this, though he did not say it in so many words, was that in its overall structure, which is that of a trip or journey described from the moment of setting out to the moment of return, and in its observer’s tone, ‘the boatride’, though written ten years earlier, prefigures

Jejuri, which was his next sequence.

A week or two after this conversation when next I spoke with Kolatkar he surprised me by saying that I should edit

The Boatride. Since the book’s contents had already been decided and there were no further poems to add, or at least none that I was aware of, my role at the time, as editor, seemed limited to ensuring that we had a good copy-text. But even this, I realised, would not be easy.

There was one poem, ‘The Turnaround’, about which Kolatkar had in the past expressed reservation, and I wondered if I should use it as it stood. In 1989, when Daniel Weissbort and I were editing

Periplus: Poetry in Translation (1993), I had asked Kolatkar for unpublished translations of his Marathi poems. He had shown me ‘The Turnaround’ on that occasion, but, unhappy about one word in it, ‘daisies’, had asked me not to include it in

Periplus. The Marathi had

vishnukranta, a common wild flower widely distributed throughout India, for which he felt ‘daisies’ was not the right equivalent. Here is the poem:

Bombay made me a beggar.

Kalyan gave me a lump of jaggery to suck.

In a small village that had a waterfall

but no name

my blanket found a buyer

and I feasted on just plain ordinary water.

I arrived in Nasik with

peepul leaves between my teeth.

There I sold my Tukaram

to buy myself some bread and mince.

When I turned off Agra Road,

one of my sandals gave up the ghost.

I gave myself a good bath

in a little stream.

I knocked on the first door I came upon,

asked for a handout, and left the village.

I sat down under a tree,

hungry no more but thirsty like never before.

I gave my name et cetera

to a man in a bullock cart

who hated beggars and quoted Tukaram,

but who, when we got to his farm later,

was kind enough to give me

a cool drink of water.

Then came Rotegaon

where I went on trial

and had to drag the carcass away

when howling all night

a dog died in the temple

where I was trying to get some sleep.

There I got bread to eat alright

but a woman was pissing.

I didn’t see her in the dark

and she just blew up.

Bread you want you motherfucker you blind cunt, she said,

I’ll give you bread.

I could smell molasses boiling in a field.

I asked for some sugarcane to eat.

I shat on daisies

and wiped my arse with neem leaves.

I found a beedi lying on the road

and put it in my pocket.

It was walk walk walk and walk all the way.

It was a year of famine.

I saw a dead bullock.

I crossed a hill.

I picked up a small coin

from a temple on top of that hill.

Kopargaon is a big town.

That’s where I read that Stalin was dead.

Kopargaon is a big town

where it seemed shameful to beg.

And I had to knock on five doors

to get half a handful of rice.

Dust in my beard, dust in my hair.

The sun like a hammer on the head.

An itching arse.

A night spent on flagstones.

My tinshod hegira

was hotting up.

The station two miles ahead of me,

the town three miles behind,

I stopped to straighten my dhoti

that had bunched up in my crotch

when sweat stung my eyes

and I could see.

A low fence by the roadside.

A clean swept yard.

A hut. An old man.

A young woman in a doorway.

I asked for some water

and cupped my hands to receive it.

Water dripping down my elbows

I looked at the old man.

The goodly beard.

The contentment that showed in his eyes.

The cut up can of kerosene

that lay prostrate before him.

Bread arrived, unbidden,

with an onion for a companion.

I ate it up.

I picked up the haversack I was sitting on.

I thought about it for a mile or two.

But I knew already

that it was time to turn around.

Apart from the problem of the copy-text, there were, in ‘The Turnaround’, passages I found mystifying. The poem is about a walking trip through western Maharashtra and Kolatkar gives the names of the towns he passes through: Kalyan, Nasik, Rotegaon, Kopargaon. Far from being a pleasant excursion – though it has its light moments – the trip turns out to be an ordeal. At Rotegaon, he says, he ‘went on trial’, but there is no mention in the poem of any crime or whether the ‘dog [that] died in the temple / where [he] was trying to get some sleep’ and the crime are connected. By the time he reached Kopargaon, it had become physically unendurable for him to continue walking: ‘My tinshod hegira / was hotting up’. But what did ‘tinshod hegira’ mean? In fact, now that I was reading it with an editorial eye, I felt there was an air of mystery hanging over not just certain passages but the whole poem. ‘[I]n realism you are down to facts on which the world is based: that sudden reality which smashes romanticism into a pulp,’ Joyce told Arthur Power. As a poet of ‘that sudden reality’, as someone who revelled in the particular and was passionate about nouns, especially proper nouns, Kolatkar gives us all the facts about the trip including the year (‘Kopargoan is a big town. / That’s where I read that Stalin was dead.’), but this only deepened the puzzle. The poem’s dramatic opening line, ‘Bombay made me a beggar’, leaves several questions unanswered. What had made him leave the city and seek the open road? Did he have a destination in mind, or even an itinerary? Was he, as his route suggests, going to the pilgrimage town of Shirdi, which is just fourteen kilometres from Kopargaon? In 1953, the year Stalin died, Kolatkar was twenty-two years old.

My last phone conversation with Kolatkar was early in the third week of September. By then he had stopped going to Café Military, an Irani restaurant in Meadows Street, where over cups of tea he routinely met with a close circle of friends on Thursday afternoons, as he had earlier met them, for more than three decades, at Wayside Inn in Kala Ghoda before the place shut down in 2002. When his condition deteriorated, his family shifted him to Pune, to the house of his younger brother, who was a doctor. He had already been in Pune ten days when I made the phone call and found that he was too weak to speak. When I persisted, a little excitedly I’m afraid, in asking him about ‘The Turnaround’, he said it was ‘an inner journey’ and mumbled something about a ‘personal crisis’. He said he’d explain everything if I came to Pune. I took the next train.

I reached Pune late in the evening of the 21st and made my way to his brother’s house in Bibwewadi. The house was in a side street, a duplex in a row of identical houses, each having a modest front yard with a motor scooter or car, often both, parked in it. Kolatkar was in an upstairs room and seemed to be asleep. The brother who was a doctor was still at his clinic, but his two other brothers, Sudhir and Makarand, were there, as was his wife Soonoo. ‘His mouth is constantly parched,’ Sudhir said, ‘and that’s affected his speech. He also cannot take in any food. But he feels a little better in the mornings. Maybe you should come back tomorrow and put your questions to him.’ Looking at Kolatkar, there wasn’t much hope of getting answers.

When I returned in the morning, I found Kolatkar was awake and, judging by the faces of those around him, ready to receive visitors. I pulled up a chair close to his bed and we resumed the phone conversation started three days ago. Speaking haltingly and with difficulty, sometimes leaving his sentences unfinished, he said that ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ and ‘The Turnaround’ had come out of the same experience. Though it seems from ‘The Turnaround’ that he went on the walking trip alone, Kolatkar said that a friend, the poet and painter Bandu Waze, had accompanied him. There is a reference to Waze, though not by name, in ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’:

Tell me why the night before we started

Dogs were vainly

Barking at the waves;

And tell my why in an unknown temple

Days and waves away

A black dog dumbly

From out of nowhere of ourselves yawned and leapt;

And leaving us naked

And shamefaced,

Tell me why the black dog died

Intriguingly between

God and our heads.

Kolatkar said that they spent the night before they started on the trip at the Gateway of India, which is where he heard the dogs ‘vainly / Barking at the waves’. They had probably slept rough on the footpath. It would be, for them, the first of many such nights.

We know little about Waze. He and Kolatkar first met in 1952, when Kolatkar was a student at the Sir J.J. School of Art. Dilip Chitre, who was a close friend of both, describes Waze as ‘a maverick, self-taught artist…with immense energy, talent, and conviction that many of his academically cultivated colleagues lacked.’ The ‘academically cultivated colleagues’ presumably referred to painters like Ambadas, Baburao Sadwelkar and Tyeb Mehta, who were students at the art school roughly at the same time as Kolatkar. In 1954, during the early difficult months of their marriage, when Kolatkar and his first wife Darshan Chhabda were living in Malad, Bombay, in a place that was little better than a shack, Waze moved in with them. His presence, at a time when Kolatkar had no job and practically no money of his own, couldn’t have made matters easier.

Makarand, whom I asked later about the walking trip, said he was then still at school but remembered Kolatkar and Waze arriving at their father’s house in Pune, unshaven and tired, looking like two sadhus. When they sat down to a meal, he said, it was as though they had not eaten in days. Indeed, accounts of eating, or more often not eating, recur throughout ‘The Turnaround’:

I arrived in Nasik with

peepul leaves between my teeth.

‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ does not mention the ‘trial’ in Rotegaon nor ‘The Turnaround’ the dogs at the Gateway of India, but both poems refer to the incident at the temple. In ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ the incident is central to the poem (‘And tell me why in an unknown temple /…A black dog dumbly,’ etc), whereas in ‘The Turnaround’, as everything else in it, the incident, stripped down to essentials, like the language itself, is mentioned in passing.

As Kolatkar now narrated it to me, there had been a series of petty thefts in Rotegaon and the suspicion of the townsfolk fell on the two tramps. Hauled up before a group of elders (this is the ‘trial’ referred to in ‘The Turnaround’), they had a hard time proving their innocence. When they were finally allowed to leave, it was on the condition that they first clean up the temple (‘drag the carcass away’) where, on the one night they had spent in it, a ‘black dog’ had died ‘Intriguingly between / God and our heads.’ Kolatkar said the dog had died at the midpoint between where they had lain down to sleep (‘our heads’) and the temple idol (‘God’).

I asked Kolatkar about ‘tinshod hegira’. He said ‘tinshod’ referred to Nana Patil’s

patri sarkar or ‘horseshoe government’. Patil was a well-known revolutionary leader during colonial times and ran a parallel government in the villages around Satara in the 1940s. Those found defying its orders and collaborating with the British had, horseshoe-fashion, tin nailed to the soles of their feet. Kolatkar, in the poem, is comparing his suffering after his hegira – or flight – from Bombay (‘It was walk walk walk and walk all the way’) with the suffering of those punished by Patil’s

patri sarkar. His feet felt as though ‘tinshod’, ‘The sun like a hammer on the head’. He was by then at the end of his tether. The poem ends on a note that, in more sense than one, is visionary:

I stopped to straighten my dhoti

that had bunched up in my crotch

when sweat stung my eyes

and I could see.

A clean swept yard.

A hut. An old man.

A young woman in a doorway.

Lying ‘prostrate’ before the old man was a ‘cut up can of kerosene’. Kolatkar now remembered that can. It was cut in half, he said, and looked as though the old man had ‘beaten the life out of it’. As he spoke, he seemed to be reliving the satoric experience of fifty years ago:

I thought about it for a mile or two.

But I knew already

that it was time to turn around.

About the ‘personal crisis’, though, which had led him to renounce the city he was returning to, he did not say anything.

There remained the matter of ‘daisies’. When I asked him about it, he said I should change it to

vishnukranta. He had looked it up in a book on flowers, he said, but to no avail. The book didn’t give the English name.

‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ is one of fourteen English poems, collectively called ‘journey poems’, written during 1953-54. Though they all came out of the same experience, the walking trip through western Maharashtra, there is nothing in the poems that identifies them with a particular landscape. It is as though, in 1953, Kolatkar had staked off his subject but not located the poetic resources to express it in. Never a man in a hurry, he was prepared to wait. The wait ended in 1967 when he wrote, in Marathi, ‘Mumbaina bhikes lavla’. Its English translation, ‘The Turnaround’, he did in 1987, to read at the Stockholm festival.

Kolatkar showed the ‘journey poems’ to his friends, one of whom, Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni, who later became a well-known art critic and writer on Marathi theatre, passed them on to Nissim Ezekiel. As editor of

Quest, a new magazine funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Ezekiel was open to submissions. He also had an eye for talent and this time, in Kolatkar, he spotted a big one. He decided to carry ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ in the magazine’s inaugural issue, which appeared in August 1955. It was Kolatkar’s first published poem in English. Around then, he and Ezekiel also met for the first time. For someone who was to spend his next fifty years in advertising, Kolatkar’s meeting with Ezekiel, fittingly enough, took place in the offices of Shilpi, where Ezekiel had a job as copywriter.

A line below ‘The Hag’ and ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’ in Chitre’s

Anthology of Marathi Poetry says ‘English version by the poet’, suggesting that the two poems are translations. I knew from previous conversations with Kolatkar that he wrote them both in English and Marathi and considered them to be as much English poems as Marathi ones. Now, in Pune, as Soonoo dabbed his lips with wet cotton wool to keep them moist, he spoke about them again. The Marathi and English versions, he said, were ‘very closely related’; ‘they can bear close comparison’. He also said he wrote them ‘side by side’. Of ‘The Hag’ and ‘Therdi’ (its Marathi title) he said he would write one line in Marathi and a corresponding line in English, or the other way round. ‘They run each other pretty close.’ He also commented on the rhyme scheme: ‘There is no discrepancy.’

Chitre, whom I’d rung up on reaching Pune, came with his wife Viju to see Kolatkar. He had with him an office file and a spiral bound book consisting of photocopies made on card paper. He asked me to look at them. He had recently finished a short film on Kolatkar for the Sahitya Akademi, and the office file and the spiral bound book, both of which Darshan had given him, were part of the archival material he’d collected. The poems in the file consisted mostly of juvenilia, and some, with their references to ‘a begging bowl’ and ‘the changing landscape’, looked like they belonged with the ‘journey poems’, which, as I found out later, they indeed did:

Destined to become a begging bowl

We let rise our clay

And holding it in our hand

Wordlessly and worldlessly

To be filled and fulfilled

We wandered

In the wilderness of our heart

and

We retreated from ourselves

To become the changing landscape

And the mutable topography

That accompanied us

And whispered in our ears

I quickly went through the poems and read them out to Kolatkar. If I liked something I asked him if I could put it in

The Boatride, and if he said yes I’d put a tick against it. The ones I ticked were ‘Of an origin moot as cancer’s’, ‘Dual’, ‘In a godforsaken hotel’, and ‘my son is dead’. The poems were typewritten and some had obvious typos. A line in ‘Dual’ read ‘the two might declare harch thorns and live’.

‘Harch’? I asked Kolatkar.

‘Harsh.’

In the list I had sent him, the one he had approved of, the ‘Poems in English’ section had eight poems. Now it had twelve. Clearly,

The Boatride was going to be a bigger book than I had anticipated; I also began to see why Kolatkar wanted it to have an editor.

In 1966, Kolatkar joined an advertising studio, Design Unit, in which he was one of the partners. It did several successful campaigns, including one for Liberty shirts, which won the Communication Artists Guild award for the best campaign of the year. The Liberty factory had recently been gutted in a fire and the copy said ‘Burnt but not extinguished’; Kolatkar did the visuals, one of which showed a shirt, with flames leaping from it. The studio was in existence for three years and everything in the spiral bound book was from this period of Kolatkar’s life. In fact, it was his Design Unit engagement diary, whose pages Darshan had rearranged and interspersed with poems, drawings and jottings. Flipping through it was like peeking into an artist’s lumber-room, crammed with bric-à-brac. It revealed more about Kolatkar’s public life as successful advertising professional and private life as poet than a chapter in a biography would have.

The first page had a drawing of a gladiolus, the curved handle of an umbrella sticking through the leaves. Other drawings showed an umbrella hanging from a sickle moon; from an antelope’s horns; from a man’s wrist; stuck in a vase; safely tucked behind a man’s ear like the stub of a pencil; placed with a cup and saucer, like a spoon, to stir the tea with. The text accompanying the drawings was always the same, ‘Keep it’. Between the drawings were jottings, scribbles, messages (‘Darshan Kolatkar 40 Daulat Send me my green shirt’), expenditure figures (‘Liquor 37.75’), memos to himself (‘plan & save cost; meetings fortnightly; how to inspire/educate artists’), names and telephone numbers of clients, appointments to keep or cancel, seemingly useless scraps of paper preserved only because those who were close to him were farsighted and valued every scrap he put pen to. One page had written in it ‘Ring Farooki’; ‘Ring Pfizer’; ‘Ring Mrs Chat. cancel 3.30 Tues. appt.’; ‘?Bandbox?’; ‘7.30 Kanti Shah’; and somewhere in the middle was also the drawing of a man with a V-shaped face and arrows for arms and legs, the right arrow-leg pointing to ‘12.00 Jamshed’. Against a drawing of a cut-out-like figure he had written, ‘Imagine he is the client you hate most and stick a pin anywhere.’ And above it, ‘Just had a frustrated meeting with a frustrated client. This fellow goes on and on. I do not like long telephonic conversations. The client is a Marwari, you know.’ In an invoice to one Mrs Mukati dated ‘9/9/67’, he had jokily scribbled ‘10,000’ under ‘Quantity’ and ‘Good mornings’ under ‘Please receive the following in good order and condition’.

The scribble on the invoice, the drawings and the poems, whether early or late, are part of the same vision. Enchanted by the ordinary, Kolatkar made the ordinary enchanting. Which is why, however familiar one may be with his work, it’s always as though one is encountering it for the first time. ‘[T]he dirtier the better’ he says of the ‘unwashed child’ in a poem in

Kala Ghoda, ‘The Ogress’, and the same might be said about the subjects he was drawn to: the humbler the better. When the ogress, as Kolatkar calls her, gives the ‘tough customer on her hands’, ‘a furious, foaming boy’, a good scrub, she has a ‘wispy half-smile’ on her face and ‘a wicked gleam’ in her eye. One imagines Kolatkar’s face bore a similar expression when he mischievously transformed the humble invoice into a cheery greeting.

What can be more uninspiring, more ordinary, or, sometimes, more enchanting, than the tall stories men tell each other when they meet in a restaurant over a cup of tea? In ‘Three Cups of Tea’ Kolatkar reproduces verbatim, in ‘street Hindi’ (and translates into American English), three such stories. He wrote the poem in 1960, at the beginning of the revolutionary decade that we associate more with Andy Warhol’s 1964 Brillo Box exhibition and the music of John Cage than with Kolatkar’s poem; more with New York than Bombay. Yet the impulse behind their works is the same, to erase the boundaries between art and ordinary speech, or art and cardboard boxes, or art and fart, whose sound Cage incorporated into his music. The impulse has its origin in Marcel Duchamp’s famous ‘ready-mades’, the snow shovels, bicycle wheels, bottle racks and urinals he picked off the peg. It was art by invoice.

By reproducing conversations heard in a restaurant in ‘Three Cups of Tea’, Kolatkar introduced the Bombay urban vernacular, the language of the bazaar, to Indian poetry; in ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’, he introduces seedy restaurant interiors and the bazaar art on their walls.

the cockeyed shah of iran watches the cake

decompose carefully in a cracked showcase;

distracted only by a fly on the make

as it finds in a loafer’s wrist an operational base.

dogmatically green and elaborate trees defeat

breeze; the crooked swan begs pardon

if it disturb the pond; the road, neat

as a needle, points at a lovely cottage with a garden.

the thirsty loafer sees the stylised perfection

of the landscape, in a glass of water, wobble.

a sticky tea print for his scholarly attention

singles out a verse from the blank testament of the table.

In 1962, when he wrote ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’, Kolatkar wouldn’t have read Walter Benjamin’s essays, which were not then available to the Anglophone world, nor would he have heard of the arcade-haunting Parisian flâneur. But as a Bombay loafer him-self, someone who daily trudged the city’s footpaths, particularly the area of Kala Ghoda, he would have recognised the figure.

‘Salo loafer!’ says a character in Cyrus Mistry’s play

Doongaji House. Over the centuries, ‘Loafer’ has almost become an Indian word of abuse, suggesting a good-for-nothing who drifts through the city in self-absorbed fashion when, in fact, he is streetwise and his keen eye doesn’t miss a thing. (Kolatkar himself seldom walked past a pavement bookstall without picking up a treasure.) This is true of the loafer even when he appears most relaxed, having tea, say, in an Irani restaurant, a portrait of ‘the cockeyed shah of iran’ displayed above the till and the whole place buzzing with flies. On these occasions, he is like a papyrologist in a library poring over a classical document, though the objects he could be studying are the tables, chairs, mirrors and bazaar prints in whose midst he sits.

The bazaar print here described – the ‘stylised perfection’ of the landscape – brings to mind some of Bhupen Khakhar’s yet unpainted early works like

Residency Bungalow (1969). In Khakhar’s painting, the bungalow is a two-storey colonial house, complete with verandah, Doric columns and pediment; ‘a lovely cottage’. Leading to it is a path, ‘neat as a needle’, with ‘elaborate trees’ on either side. In the background are more trees, painted in the same ‘elaborate’ fashion. In the foreground, where the ‘crooked swan’ might have been, is the painter’s friend, Gulammohammed Sheikh, sitting very stiffly in a chair, leaning a little to his right, his arm resting on a round table. Behind him, sitting on a platform attached to the house, are smaller figures. Pop art was an influence on Khakhar, and it is not surprising that both he and Kolatkar responded to bazaar prints. They were, in their different mediums, responding to the spirit of the age.

Residency Bungalow was the house in Baroda that Khakhar and Sheikh shared, along with other painter friends of theirs. And it was from this house, which belonged to Baroda University where Sheikh taught at the art school, that Sheikh and Khakhar brought out their A4-sized little magazine

Vrischik (1969-1973), which means

scorpion in Gujarati. Among those whose work appeared in its pages was Kolatkar, who contributed translations of Namdeo, Janabai and Muktabai to a special issue of

Vrischik (Sept-Oct 1970) on bhakti poetry. As Ezra Pound (from St Elizabeth’s Hospital, Washington DC) wrote to Chak (‘Dear Chak’), that is Amiya Chakravarty, ‘“All flows” and the pattern is intricate.’

Wayside Inn where Kolatkar held court on Thursday afternoons for many years (it closed down in 2002).

The view from a restaurant rather than a restaurant interior is the subject of

Kala Ghoda Poems. On most days, around breakfast time and again in the late afternoon, after the lunch crowd had left, Kolatkar could be found at Wayside Inn in Rampart Row. He would usually be alone, except on Thursday afternoons, when all those who wished to see him joined his table and there could be as many as fifteen people around it. Sometime in the early 1980s, the idea of writing a sequence of poems on the street life of Kala Ghoda, encompassing its varied population (the lavatory attendant, the municipal sweeper, the kerosene vendor, the beggar-cum-tambourine player, the drug pusher, the shoeshine, the ‘ogress’ who bathes the baby boy, the idli lady, the rat-poison man, the cellist, the lawyer), its animals (pi-dog, crow), its statuary (David Sassoon), its commercial establishments (Lund & Blockley) and its buildings (St Andrew’s church, Max Mueller Bhavan, Prince of Wales Museum, Jehangir Art Gallery ), began to take shape in his head. Asked in 1997 by Eunice de Souza, how he managed to write a poem like ‘The Ogress’, in which both the woman and the boy she’s bathing ‘emerge as complete human beings’, Kolatkar replied, ‘It’s a secret.’* The secret, I think, lay in the gift he had of making completely impersonal the scene he was imaginatively engaging with while at the same time, eschewing all isms and ideologies, identifying closely with each part. By the time he finished the sequence in 2004, to quote Joyce’s famous remark to Frank Budgen about Ulysses, it gave a picture of Kala Ghoda ‘so complete that if it one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of [his] book’.

The name Kala Ghoda (काळा घोडा in Marathi), meaning black horse, came from the black stone statue of King Edward VII mounted on a horse which used to stand in Kala Ghoda Square.

The first time I heard Kolatkar read was at Jehangir Art Gallery in 1967. Two years earlier, at Gallery Chemould in the same premises, Khakhar had exhibited his first collages, their inspiration the vividly coloured oleographs that had fascinated him since boyhood. I cannot now recall what the occasion was nor, apart from the painter Jatin Das, who else read that evening, but Kolatkar read a poem that he seemed to have improvised on the spot. It began ‘My name is Arun Kolatkar’ and was over in less than a minute. He left immediately afterwards, making his way to one of the Colaba bars, for he was, in the late 1960s, for about two and a half years, a heavy drinker, stories of which are still told by those who knew him at the time.

To my surprise, the poem was in the Design Unit diary, written out in his neat hand. He said I could include it in

The Boatride, then added, referring to the poem, ‘It’s a disappearing trick.’ There were also other poems in the diary which I thought were worthy of inclusion: ‘Directions’, a “found” poem similar to ‘Three Cups of Tea’ but in a quite different linguistic register, was one and ‘today i feel i do not belong’, which makes the only reference to advertising in his poetry (‘i’m god’s gift to advertising / is the refrain of my song’), another. For the most part, though, the diary consisted of ideas for future poems (‘Write a bloody poem called beer. Make it bloody.’), notes and fragments in English and Marathi, and quick verbal sketches that captured a domestic moment or something he’d seen while walking idly down a road. For Kolatkar, writing was a zero waste game; no thought that passed through his mind went unnoted.

Once we got the rat behind the trunk, all we had to do was ram it against the wall.

*

It was dark

Arun woke up

D was asleep

the sound of the ceiling fan

gets mixed up

with the sound of the elevator

*

your sulky lips are prawns

fork them with a shining smile

*

on the same tile of the footpath

where that schoolgirl is standing

a mad woman sat yesterday scratching with her nail

a rotten cunt

and a big festering wound

on her shaven head

*

Leap clear, my lion, through

the ring of fire. Mind the mane,

the hind legs and the tail.

Do it again.

I wanted to ask Kolatkar about these poems and fragments but his voice had grown faint and he closed his eyes. It was time to leave. As we slipped out of the room, a message came from the kitchen downstairs that lunch was ready.

The following day, on my way to see him, I wondered if we had not already had our last conversation. Still, in the hope that he might be able to talk, I was carrying with me the original list of thirty-two poems for

The Boatride, since added to, as well as the diary. But Kolatkar had other things on his mind.

He spoke about American popular music and its influence on him. He said that gangster films, cartoon strips and blues had shaped his sense of the English language and he felt closer to the American idiom, particularly Black American speech, than to British English. He mentioned Bessie Smith, Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters – ‘Their names are like poems,’ he said – and quoted the harmonica player Blind Sonny Terry’s remark, ‘A harmonica player must know how to do a good fox chase.’ One reason why he liked blues, he said, was that the musicians were often untrained and improvised as they went along. He dwelt on the music’s social history: how during the Depression blues performers moved from place to place, playing in honky-tonks, sometimes under the protection of mobsters. He remembered the Elton John song ‘Don’t shoot me I’m only the piano player’.

Blues (though it can have a spiritual side) and bhakti poetry are, in intent, markedly different from each other. One belongs to the secular world; the other addresses itself to god. There are, however, parallels between them. Each draws its images from a common pool, each limits itself to a small number of themes that it keeps returning to, and each speaks in the idiom of the street. They can sound remarkably alike.

It’s a long old road, but I’m gonna find the end.

It’s a long old road, but I’m gonna find the end.

And when I get there I’m gonna shake hands with a friend.

could be Tukaram but is Bessie Smith, just as ‘Get lost, brother, if you don’t / Fancy our kind of living’ could be blues but are the lines of a Tukaram song, in Kolatkar’s ‘blues’ translation. In his use of diction, Kolatkar saw himself very much in the blues-bhakti tradition. He once said to me that he wrote a Marathi that any Marathi-speaker could follow. He also said that he was not finished with a translation until he had made it look like a poem by Arun Kolatkar.

The parallels between Kolatkar’s work and blues do not end there. Here is the blues singer Tommy McClennan, standing beside a road in the Mississippi delta, waiting for a bus in the hot sun:

Here comes that Greyhound with his tongue hanging out on

the side.

Here comes that Greyhound with his tongue hanging out on

the side.

You have to buy a ticket if you want to ride.

And here is Kolatkar in

Jejuri:

The bus goes round in a circle.

Stops inside the bus station and stands

purring softly in front of the priest.

A catgrin on his face

and a live, ready to eat pilgrim

held between its teeth.

(‘The Priest’)

Observe, too, the stanza unit. It was with the development of the three-line verse, which Kolatkar uses here and throughout much of

Kala Ghoda Poems, that the blues became a distinctive poetic form.

After Elton John’s ‘Don’t Shoot Me’, Kolatkar recalled some more songs: Big Mama Thornton’s ‘Hound Dog’ and Elvis Presley’s ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and ‘Money Honey’. His voice, which so far had been a whisper, suddenly grew loud as he almost sang out the words:

You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog cryin’ all the time.

You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog cryin’ all the time.

Well, you ain’t never caught a rabbit and you ain’t no friend

of mine.

and

Well, you can knock me down,

Step in my face…

Do anything that you want to do, but uh-uh,

Honey, lay off of my shoes

Don’t you step on my blue suede shoes.

and

You know, the landlord rang my front door bell.

I let it ring for a long, long spell.

I went to the window,

I peeped through the blind,

And asked him to tell me what’s on his mind.

He said,

Money, honey.

Money, honey.

Money, honey, if you want to get along with me.

He said he had a record collection of about 75 LPs, which he gifted to the National Centre for the Performing Arts.

He would have gifted them, in all likelihood, in 1981, when he moved house from Bakhtavar in Colaba, where he had lived since 1970, to a much smaller one-room apartment in Prabhadevi, Dadar. Around then, he also sold off his substantial collection of music and science fiction books. The first time I visited him in Prabhadevi, I was surprised that there were hardly any books in the room. I especially missed the volumes of American and European poets, which he kept in a glass-front bookcase in Bakhtavar and which I would eye enviously each time I passed them. Those, he said, he had not sold off but because of the shortage of space had put them in storage with a friend. I remember asking if he regretted not having his books with him and he said that having them in his head was more important than their physical presence. This particular conversation with him came back to me recently while reading Susan Sontag’s essay on Canetti, ‘Mind as Passion’. To interpolate from it, Kolatkar’s passion for books was not, as it was for Walter Benjamin, ‘a passion for books as material objects (rare books, first editions).’ Rather, the ‘ideal’ was ‘to put the books inside one’s head; the real library is only a mnemonic system.’ To this library in the head, because of his prodigious memory, Kolatkar, at all times, had complete access. I never saw him reach out for a book, but whenever he spoke about one, whether it was a Latin American novel,

The Tale of the Genji, or a Sanskrit

bhand, it was as though he had it open in front of him, and if he remembered a funny passage would, while narrating it, almost roll on the floor, gently slapping his thighs.

Kolatkar may not have had space for books, but he continued to buy them as before, on a scale that would match the acquisitions of a small city library. (He purchased newspapers on the same scale too; five morning and three evening papers every day.) He bought books, read them, and passed them on to his friends. This is how I acquired my copy of Marquez’s

Love in the Time of Cholera, which he had bought in hardback soon as it became available at Strand Book Stall.

It was only a matter of time before books reappeared in his apartment, covering a wall from end to end. Scanning the titles, I found no poetry or fiction; instead, history. When, in her interview with him, Eunice de Souza remarked on the books on Bosnia on his shelves, Kolatkar dwelt at length on his reading habits:

I want to reclaim everything I consider my tradition. I am particularly interested in history of all kinds, the beginning of man, archaeology, histories of everything from religion to objects, bread-making, paper, clothes, people, the evolution of man’s knowledge of things, ideas about the world or his own body. The history of man’s trying to make sense of the universe and his place in it may take me to Sumerian writing. It’s a browser’s approach, not a scholarly one; it’s one big supermarket situation. I read across disciplines and don’t necessarily read a book from beginning to end. I jump back and forth from one subject to another. I find reading documents as interesting as reading poetry. I am interested in the nature of history, which I find ambiguous. What is history? While reading it one doesn’t know. It’s a floating situation, a nagging quest. It’s difficult to arrive at any certainties. What you get are versions of history, with nothing final about them. Some parts are better lit than others, or the light may change, or one may see the object differently. I also like looking at legal, medical, and non-sacred texts – schoolboys’ texts from Egypt, a list of household objects in Oxyrhincus, a list of books in the collection of a Peshwa wife, correspondence about obtaining a pair of spectacles, deeds of sale, marriage and divorce contracts. One dimension of my interest in all this is literary, for example, in the Bible as literature. The Song of Solomon goes back to Egypt and Assyria. I like following these trails.

Like all autodidacts, Kolatkar’s dream was to know (‘to reclaim’) everything, to hold all knowledge, like a shining sphere, in the palm of the hand. Nor did he give up reading fiction altogether. One winter I was in Bombay he was reading W.G. Sebald’s

Austerlitz.

He read widely, and if a question interested him, he would track down everything there was on it. When he was contemplating a poem on Héloïse for

Bhijki Vahi (2003), each of whose twenty-five poems is centred around a sorrowing woman – from Isis, Cassandra and the Virgin Mary to Nadezhda Mandelstam, Susan Sontag, and his own sister, Rajani, who lost her only son, a cadet pilot in the Indian Air Force, in an air crash – he collected a shelfful of books on the subject. Eventually he abandoned the idea of writing on Héloïse, saying to me that he had not been able to find a way into the story, by which he meant a new perspective on it that would make it different from a retelling. He faced a similar problem with Hypatia of Alexandria, which he solved by making St Cyril, who is thought to have had a hand in her murder, the poem’s speaker.

At 393 pages,

Bhijki Vahi (which translates as

Tear-stained Notebook) is among all of Kolatkar’s works the longest. It is also the most complex. Just to enumerate the books and authors he read for it is to outline a course in world literature. For ‘Trimary’ (Three Maries), the New Testament; for ‘Laila’, Fuzuli’s

Leyla and Mejnun in Sofi Huri’s translation (Kolatkar said he found the introductory essay by Alessio Bombaci on the history of the poem particularly useful); for ‘Apala’, the

Rg Veda,

Rg Vedic Darshan and Chitrao Shastri’s

Prachin Charitra Kosh; for ‘Isis’, E.A. Wallis Budge; for ‘Cassandra’, Homer, Virgil, Robert Graves and Robert Payne (

The Gold of Troy); for ‘Muktayakka’, the

Sunyasampadane; for ‘Rabi’a’, Farid-ud-Din Attar and Margaret Smith; for ‘Hypatia’, Edmund Gibbon, Charles Kingsley, E.M. Forster and Maria Dzielska; for ‘Po Chu-i’, Arthur Waley; for ‘Helenche guntaval’ (Helen’s Hair), Robert Payne and Peter Green (

Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age); for ‘Kannagi’, Alain Danielou’s translation of

Shilappadikaram and Gananath Obeyesekere’s

The Cult of the Goddess Pattini; for ‘Nadezhda’, her two volumes of autobiography and Mandelstam’s prose; and for ‘Susan’, Susan Sontag’s

On Photography. ‘Hadamma’ was based on an Inuit folktale and ‘Maimun’, the Qureshi girl from Haryana who was the victim of an honour killing in 1997, on a clutch of newspaper reports. The story was still being reported in the Indian press when Kolatkar wrote the poem. In ‘Ashru’ (Tears), the first poem in the book, he uses the word ‘lysozyme’, an enzyme found in human tears and egg white, which he came across in a newspaper article on the work of the molecular biologist Francis Crick, and ‘Kim’ is a reference to Nick Ut’s famous 1972 photograph showing nine-year-old Kim Phuc fleeing her village outside Saigon after a napalm attack. He does not provide the poems with notes, but had he done so, the eclecticism of his sources would be reminiscent of Marianne Moore.

Bhijki Vahi won the Sahitya Akademi Award in Marathi but otherwise the critics, daunted by its range of references, greeted it with silence. Kolatkar, unfortunately, never got round to translating its poems into English. ‘Sarpa Satra’, the penultimate poem in the book, appears to be an exception but it is not. I asked him about it now and he said that he started writing it in Marathi first but, compelled by the subject, also decided to write it in English. Like ‘The Hag’ and ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’, it exists independently in both languages.

Based in the frame story of the

Mahabharata,

Sarpa Satra is also a contemporary tale of revenge and retribution, mass murder and genocide, and one person’s attempt to break the cycle. In the story, the divine hero Arjuna decides, ‘Just for kicks, maybe’, to burn down the Khandava forest. In a passage of great lyrical beauty, Kolatkar describes the conflagration in which everything gets destroyed, ‘elephants, gazelles, antelopes’ and

people as well.

Simple folk,

children of the forest

who had lived there happily for generations,

since time began.

They’ve gone without a trace.

With their language

that sounded like the burbling of a brook,

their songs that sounded like the twitterings of birds,

and the secrets of their shamans

who could cure any sickness

by casting spells with their special flutes

made from the hollow

wingbones of red-crested cranes.

Among those who die in the ‘holocaust’ is a snake-woman, to avenge whose loss her husband, Takshaka, kills Arjuna’s grandson, Parikshit. Parikshit’s son, Janamejaya, then holds the snake sacrifice, the Sarpa Satra, to rid the world of snakes: ‘My vengeance will be swift and terrible. / I will not rest / until I’ve exterminated them all.’ Though the mass killing of snakes symbolically represents the many genocides of the last century, Kolatkar, by taking a story from an ancient epic, brings the whole of human history under the scrutiny of his moral vision. In the

Mahabharata, Aasitka, whose mother is herself a snake-woman and Takshaka’s sister, is able to stop the sacrifice midway, but Kolatkar’s poem offers no such consolation:

When these things come to an end,

people find

other subjects to talk about

than just

the latest episode of the Mahabharata

and the daily statistics of death;

rediscover simpler pleasures –

fly kites,

collect wild flowers, make love.

Life seems

to return to normal.

But do not be deceived.

Though, sooner or later,

these celebrations of hatred too

come to an end

like everything else,

the fire – the fire lit for the purpose –

can never be put out.

In July 2004, as we were on our way by taxi from Prabhadevi to Café Military, Kolatkar, looking out of the taxi window and then at me, remarked on his English and Marathi oeuvres. With the exception of

Sarpa Satra, he said, his stance in ‘the boatride’,

Jejuri and

Kala Ghoda Poems had been that of an observer; he was on the outside looking in. He wondered whether he’d have gone on writing the same way if he’d lived for another ten years. The Marathi books, on the other hand, were all quite different, he said, and there was no obvious thread connecting

Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita, Chirimiri and

Bhijki Vahi.

But there’s something else, too, that links ‘the boatride’,

Jejuri and

Kala Ghoda Poems. Each of them is arranged in the cyclic shape of the Ouroboros, their last lines suggestingly leading to their opening ones.

Jejuri begins with ‘daybreak’ and ends with the ‘setting sun / large as a wheel’. Similarly,

Kala Ghoda Poems begins with a ‘traffic island’ ‘deserted early in the morning’ and ends with the ‘silence of the night’, the ‘traffic lights’ ‘like ill-starred lovers / fated never to meet’. In ‘the boatride’, the boat jockeys ‘away / from the landing’ and returns to the same spot when the ride is over. It will fill up with tourists and set off again, just as the state transport bus in Jejuri, at the end of the ‘bumpy ride’, will deliver a fresh batch of ‘live, ready to eat’ pilgrims to the temple priest.

His Bombay friends had meanwhile been arriving through the morning to see Kolatkar. It was a Thursday, and the crowd around his bed – Adil Jussawalla, Ashok Shahane, Raghoo Dandavate, Kiran Nagarkar, Ratnakar Sohoni – was a little like the Thursday afternoon crowd around his table at Wayside Inn. Also in the room were Dilip and Viju Chitre. Sohoni was Kolatkar’s Prabhadevi neighbour and had known him since his Design Unit days. He was carrying an accordion file, bulging with papers, which he handed over to me. Separately, he also gave me a letter. It was from Edwin Frank, the editor of the NYRB Classics Series. Frank had been in touch with Kolatkar over

Jejuri, which he acquired for the series in May 2004. When

Kala Ghoda Poems and

Sarpa Satra appeared, Kolatkar had sent him the books and Frank’s letter was an acknowledgement. I read it out.

September 3, 2004

Dear Mr Kolatkar,

Many thanks for sending me Sarpa Satra and the long awaited Kala Ghoda poems. I have read both books with enormous pleasure and look forward to doing so again many times. The acuteness of description, the attentive humanity, and the humour are all extraordinary; above all, I am struck by how the poems, as true poems will, succeed in making time – a time in which the world becomes real and welcome and which they offer to the reader as a gift. Here’s to idlis!

I also want to say how beautifully put together the two books are. And many thanks for the signed copy of Jejuri which Amit Chaudhuri has forwarded to me.

I cannot read Marathi, I am sad to say, but are there any English translations of any of the poems you have written in that language? Pras Prakashan’s brief description makes me eager to find out what I can.

Where, finally, should I turn to purchase additional copies of the two new books?

With deepest appreciation and admiration,

Yours,

Edwin Frank

‘Nice letter,’ Kolatkar said after I finished reading it. And after a pause, ‘What did you say about September?’

‘September 3. It’s the date on the letter,’ I said.

The NYRB edition of Jejuri.

During my visit to Bombay in July, I had told Kolatkar that I would try and visit him again in August. I couldn’t go, but in anticipation of my coming he had set aside the poems which he wanted me to see, putting them in the accordion file. The first folder I pulled out from it was marked ‘Drunk & other songs. Late sixties, early seventies’. This was the period when Kolatkar’s interest in blues, jazz and rock ’n’ roll took a new turn. He learnt musical notation and took lessons in the guitar and, from Arjun Shejwal, the pakhawaj, and started to write songs, recording, in 1973, a demo consisting of ‘Poor Man’, ‘Nobody’, ‘Joe and Bongo Bongo’ and ‘Radio Message from a Quake Hit Town’. Three of these are “found” songs, further examples of Kolatkar’s transformations of the commonplace. ‘Joe and Bongo Bongo’ and ‘Radio Message from a Quake Hit Town’ were based on newspaper reports and ‘Poor Man’ took its inspiration from the piece of paper that beggars thrust before passengers waiting in bus queues and at railway stations. It gives the beggar’s life story and ends with an appeal for money. ‘Poor Man’ has an

ananda-lahari in the background, an instrument that is popular with both beggars and mendicants, particularly the Baul singers of Bengal. While its plangent music is truthful to the origin of the song, the beggar’s appeal, it also provides a nice contrast to the outrageous lyrics in which the ‘poor man from a poor land’ is an aspiring rock star, who is singing not for his next meal but because he wants ‘a villa in the south of france’ and ‘a gold disk on [his] wall’.

In October 1973, one of Kolatkar’s friends, Avinash Gupte, who was travelling to London and New York, tried to interest agents and music companies there in the demo but nothing came of the effort. Kolatkar’s shot at the ‘gold disk’ had ended in disappointment and he abandoned all future musical plans. He filed away the ‘Drunk & other songs’, never to return to them again. Instead, in November-December of that year, he sat down and wrote

Jejuri, completing it in a few weeks.

One by one, I read out the ‘Drunk & other songs’, many of which I was seeing for the first time. I wanted to know which ones to include in The Boatride and, in case there was more than one version, which version to use. I read them in the order I found them.

tape me drunk

my sister

my chipmunk

spittle spittle spittle

gather my spittle

but never in a hospital

don’t tie me down

promise me pet

don’t tie me down

to a hospital bed

my salvation i believe

is in a basket of broken eggs

yolk on my sleeve

and vomit on my legs

o world

what is my worth

o streets

where is my shirt

begone my psychiatrist

boo

but before you do

lend me your trousers

because in mine i’ve pissed

‘That sounds honourable enough,’ Kolatkar joked after I’d finished reading it. I read out the next one:

hi constable tell me what’s your collar size

same as mine i bet this shirt will fit you right

the shirt is yours feel it don’t you like the fall

all you got to do to get it is make one phone call…

‘Drunk,’ he said, by way of categorising the song. During his drinking days, Kolatkar had had his run-ins with the police, being picked up for disorderly behaviour on at least one occasion. Years later, he recalled the jail experience in

Kala Ghoda Poems:

Nearer home, in Bombay itself,

the miserable bunch

of drunks, delinquents, smalltime crooks

and the usual suspects

have already been served their morning kanji

in Byculla jail.

They’ve been herded together now

and subjected

to an hour of force-fed education.

(‘Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda’)

But the poems I was reading to him from the folder were nearer in time to the experience they described:

nothing’s wrong with me man i’m ok

it’s just that i haven’t had a drink all day

let me finish my first glass of beer

and this shakiness will disappear

you’ll have to light my cigarette i can’t strike a match

but see the difference once the first drink’s down the hatch

‘Straight drunk,’ came his response, quickly. To other songs, after hearing the first line, he said I could decide later whether to include them or not and to those towards the end he said ‘Skip’. Barring two, I have included all the songs in the folder. They appear in a separate section, ‘Words for Music’.

A second folder contained his translations from Marathi, six of which I had not seen before, ‘Malkhamb’, ‘Buildings’ and the four ‘Hospital Poems’. In a note given on the same sheet as the poem, Kolatkar says that ‘

malkhamb’ ‘means, literally, “a wrestler’s pole”. It’s a smooth, wooden, vertical pole buried in the ground. A common feature found in all Indian gyms. Used by wrestlers in training and by gymnasts to display their skill.’ Remembering his boyhood in Kolhapur, Kolatkar said that he used to be quite good at the

malkhamb.

The ‘Hospital Poems’ were not a typescript but a photocopy from a magazine and I asked him where they’d been published. He said ‘Santan’. I wondered what he meant and Adil helped me out. He said that the poems had appeared in Santan Rodriguez’s magazine

Kavi, which had brought out a special Kolatkar number in 1978.

Referring to ‘The Turnaround’, Kolatkar said that the book in which he’d looked for the English equivalent of

vishnukranta was in the accordion file. ‘It has a description of the flower,’ he said. I hadn’t had a chance to explore the file but did so now and found

Flowers of the Sahayadri (2001) by Shrikant Ingalhalikar in one of the pockets.

‘Your work is in good hands,’ Adil said to Kolatkar, and repeated the sentence. He believes he saw Kolatkar smile.

Sohoni, at Kolatkar’s behest, had done some photography for the cover of

The Boatride and he showed him the pictures. They were shots of boats at the Gateway of India:

where the sea jostles

against the wall

vacuous sailboats snuggle

tall and gawky

their masts at variance

islam

mary

dolphin

their names appearing

music

(‘the boatride’)

Kolatkar looked at them without saying anything. Then Ashok Shahane asked him something to which he replied that they could discuss it once he returned to Bombay. It was the last thing he said this side of silence. He died two days later, around midnight.

*

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra was born in Lahore in 1947, the year India became independent and Lahore became a part of the newly formed nation of Pakistan. His family – caught up in the enormous human dislocation that followed after Independence – abandoned Lahore for the city of Allahabad, where his father set up a dental practice. Author of four collections of poetry in English and one of translations from the Prakrit, Mehrotra has edited several books including the influential

Oxford India Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets (1991) and

An Illustrated History of Indian Literature in English (Columbia University Press, 2003). He is head of the Department of English at the University of Allahabad, and was nominated for the chair of Oxford Professor of Poetry in 2009, coming second behind Ruth Padel who resigned a week later.

Arun Kolatkar's

Collected Poems in English, edited by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, is published by Bloodaxe Books, and can be ordered immediately from Amazon.co.uk via

this link.

ARUN KOLATKAR: TWO POEMS

An Old Woman

An old woman grabs

hold of your sleeve

and tags along.

She wants a fifty paise coin.

She says she will take you

to the horseshoe shrine.

You’ve seen it already.

She hobbles along anyway

and tightens her grip on your shirt.

She won’t let you go.

You know how old women are.

They stick to you like a burr.

You turn around and face her

with an air of finality.

You want to end the farce.

When you hear her say,

‘What else can an old woman do

on hills as wretched as these?’

You look right at the sky.

Clear through the bullet holes

she has for her eyes.

And as you look on

the cracks that begin around her eyes

spread beyond her skin.

And the hills crack.

And the temples crack.

And the sky falls

with a plateglass clatter

around the shatter proof crone

who stands alone.

And you are reduced

to so much small change

in her hand.

Pi-dog

1

This is the time of day I like best,

and this the hour

when I can call this city my own;

when I like nothing better

than to lie down here, at the exact centre

of this traffic island

(or trisland as I call it for short,

and also to suggest

a triangular island with rounded corners)

that doubles as a parking lot

on working days,

a corral for more than fifty cars,

when it’s deserted early in the morning,

and I’m the only sign

of intelligent life on the planet;

the concrete surface hard, flat and cool

against my belly,

my lower jaw at rest on crossed forepaws;

just about where the equestrian statue

of what’s-his-name

must’ve stood once, or so I imagine.

2

I look a bit like

a seventeenth-century map of Bombay

with its seven islands

not joined yet,

shown in solid black

on a body the colour of old parchment;

with Old Woman’s Island

on my forehead,

Mahim on my croup,

and the others distributed

casually among

brisket, withers, saddle and loin

– with a pirate’s

rather than a cartographer’s regard

for accuracy.

3

I like to trace my descent

– no proof of course,

just a strong family tradition –

matrilineally,

to the only bitch that proved

tough enough to have survived,

first, the long voyage,

and then the wretched weather here

– a combination

that killed the rest of the pack

of thirty foxhounds,

imported all the way from England

by Sir Bartle Frere

in eighteen hundred and sixty-four,

with the crazy idea

of introducing fox-hunting to Bombay.

Just the sort of thing

he felt the city badly needed.

4

On my father’s side

the line goes back to the dog that followed

Yudhishthira

on his last journey,

and stayed with him till the very end;

long after all the others

– Draupadi first, then Sahadeva,

then Nakul, followed by Arjuna and,

last of all, Bhima –

had fallen by the wayside.

Dog in tow, Yudhishthira alone plodded on.